Pysanky symbolize miracle of life at Ukrainian Easter

COFFEE WITH WARREN, with Warren Harbeck

Cochrane Eagle, March 31, 2010

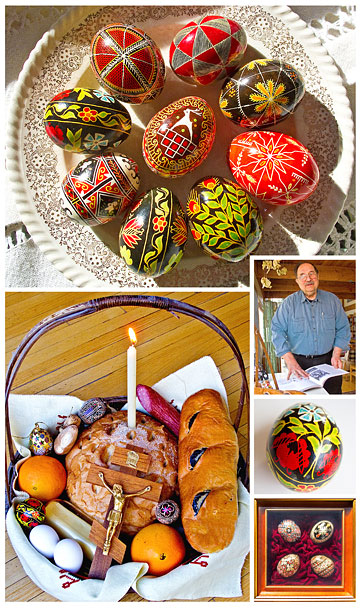

For Cochrane resident Roman Fodchuk, pysanky reflect the heart of his Ukrainian heritage. Clockwise from top: an assortment of hand-painted eggs, some by his late wife; Roman pointing to his book, Zhorna; a pysanka with his family motif of red flowers and greenery against black; a frame of four pysanky designed by his late mother; an Easter basket of eggs, kalach and other foods, with a slant-beamed Orthodox cross and a candle representing Christ the Light.

Photos by Warren Harbeck

Click on the image for a larger version

Folks don’t have to travel way up to Vegreville to gain an appreciation of pysanky. All they need do is have a visit with Roman Fodchuk, Cochrane coffee companion and acknowledged authority on things Ukrainian. He’s become my personal mentor in these beautiful hand-painted Ukrainian Easter eggs that brighten this holy season with their colours and traditions.

Yes, Vegreville may have the world’s largest pysanka as its landmark, but Roman wrote the book on the Ukrainian settlers who are the reason for the landmark. (He also oversaw planning of the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village near Edmonton.) His ancestors arrived in east-central Alberta a century ago. He’s documented much of their resourcefulness in Zhorna: Material Culture of the Ukrainian Pioneers (University of Calgary Press, 2006).

Roman’s a wellspring of insights into the religious significance of pysanky, a breathtaking feature of Ukrainian heritage.

(There is no Ukrainian church in Cochrane. Roman is a member of the St. Vladimir’s Ukrainian Orthodox Congregation in Calgary. Their church, with its five distinctive pear-shaped copper domes, dominates the hillside north of the Bow River across from the downtown core.)

Over the past few weeks Roman has given me a first-hand look at his personal collection of pysanka art and allowed me to take photos which I’m including with this column.

|

“(Pysanky are) about resurrection and ascension, an expression of this wonderful gift of God: life” |

|

“The egg was a symbol of the rebirth of the earth in pagan celebrations of spring,” Roman explained. After Ukraine embraced Christianity in 988 A.D., the egg became a symbol of the rebirth of people and “a declaration of the resurrection of Christ.”

During the week leading up to Easter, eggs are painstakingly decorated using a beeswax batik method – the designs are “written” on, not painted on. Motifs draw from ancient iconography, folklore, nature and Christianity (triangles, diamonds, sun, birds, flowers, deer, cross, etc.).

Colours can be highly symbolic, he said. “For example, red symbolizes the blood of Christ, redeeming the world through His blood shed at His crucifixion.”

Pysanky are about community. Some of them are shared among friends and relatives, while others are included in a basket with specially prepared breads (kalach and paska), fruit and other foods to be blessed by the priest at the Paschal Vigil the evening before Easter, Roman said. That basket of blessed goodies becomes the first food eaten Easter morning in celebration of the resurrection of Christ.

Some of the blessed eggs and other food are then taken to cemeteries. There “they are offered to the deceased’s relatives and friends of the family at a graveside ceremony.”

Pysanky also become treasured objects of kids’ Easter egg hunts.

Roman’s ancestors came from the Carpathian Mountains of western Ukraine. Known as Bukovynians and Hutsuls, some of them insisted on maintaining the pysanka tradition in Alberta because they believed “as long as egg decorating continues, the world will exist.”

For Roman, however, the pysanka symbolizes “the miracle of life.” Pysanky are “about resurrection and ascension, an expression of this wonderful gift of God: life – it’s one continuous thing.”

© 2010 Warren Harbeck

JoinMe@coffeewithwarren.com