Composer celebrated listening with heart and silence

COFFEE WITH WARREN, with Warren Harbeck

Cochrane Eagle, July 27, 2011

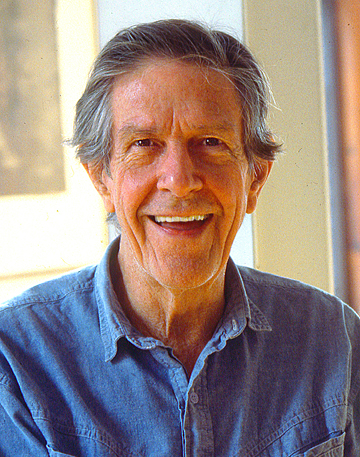

John Cage (1912–1992), American composer.

His composition consisting of four minutes 33 seconds of silence celebrated intentional listening to life around us.

Photo by James Daubney

This is the fourth in a series on being present through attentive listening. But what does silence have to do with it?

The topic of listening was suggested by David Irvine in our column of July 6 on life-breathing connection.

“Listen carefully as you feel with people,” he said. “What are their dreams? What matters to them?”

In the following week’s column, photographer Jack Blair shared with us his views on intentional listening with heart and lens. Then in last week’s column, artist Doug Driediger spoke of listening with heart, pen and brush.

This idea of heartfelt listening so piqued the imagination of another of our local readers, James Daubney, that he spent an hour with me over coffee the other day getting me to consider the importance of silence for listening.

Jim is a semi-retired professional photographer who has specialized in poster-size images of Canada’s mountain parks.

But it was another of his photographic projects that was on his mind at coffee: his portraits of his friend, the late John Cage, American avant-garde composer famous for his controversial composition, 4'33" – pronounced “four minutes 33 seconds” – of silence.

Jim described for me how 4'33" was first performed in 1952.

The pianist who introduced Cage’s work at Woodstock, N.Y., sat down at the piano and spread the score out in front of him. Then he pulled out a stopwatch and, as he lowered the lid over the keys, started timing. The watch began ticking off four minutes and 33 seconds. During that time there was no intentional sound, either from the piano or from the musician, who sat motionless except for his action of turning the pages of the score through the composition’s three movements. At the end of that time, he stopped his watch and reopened the keyboard, to the stunned reaction of a not-entirely pleased audience, who weren’t sure whether they’d just been conned into hearing . . . nothing!

For Cage, however, this was really not about silence at all, Jim explained. It was about the stillness that allows people to hear the sounds around them: the sounds of nature, of traffic – and of people.

As the composer himself explained, there really is no such thing as silence. But such experimental music as his could liberate an audience to experience the freedom of undistracted attentiveness – a stillness that transports the listener “to the moment where he is.” (See Cage’s autobiographical essay.)

This made sense to me in view of the many folks we encounter today who have their heads glued to earphones entertaining them with the latest tunes but deafening them to the sounds of birds, approaching vehicles and the voices of friends and family.

Jim’s friendship with Cage began in 1983 when the composer was at the Banff Centre. The following year he visited Cage at his Sixth Ave. loft in New York City, where he took the photo that accompanies this column.

“Knowing him was a rare gift,” Jim told me. “His apartment was a haven of serenity, many green plants, amazing ideas – and no piano and no stereo system; just the sounds of Sixth Ave., which he loved.

“His approach to music had much to do with letting sounds be themselves.”

© 2011 Warren Harbeck

JoinMe@coffeewithwarren.com