On the 50th anniversary of our arrival in Stoney Country

COFFEE WITH WARREN, with Warren Harbeck

Cochrane Eagle, October 29, 2015

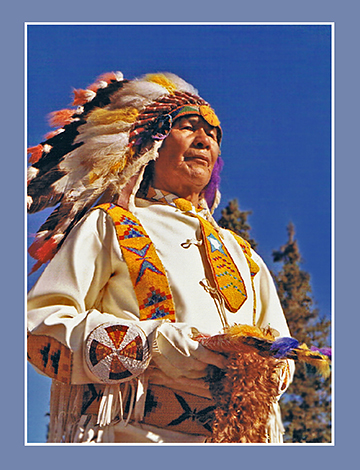

The late Stoney Nakoda Elder Jacob House was named Dathagen (“Frozen One”), but his hospitality to this columnist, whom he called mîchîksi (“my son”), was anything but cold. Photo by Warren Harbeck

Fifty years ago next week, my wife Mary Anna and I moved to Morley, the heart of the Stoney Nakoda First Nation. Thus began our amazing relationship with a community who have privileged us to enter into the very heart and soul of their amazing language and culture.

Members of the Stoney Nakoda Nation had invited us, as linguistic consultants, to assist in developing a writing system for their previously unwritten dialect of the Dakota (Sioux) language family, and in translating the Bible into Stoney.

They welcomed us warmly, making us feel right at home, not as “Whiteman” outsiders, but as fellow human beings.

In gratitude for the warm welcome we’ve experienced, I’d like to share the story of how one Stoney elder received his traditional name.

A couple of years into our time in Stoney Country, we resided for a while in the satellite community of Big Horn, located along the North Saskatchewan River an hour west of Rocky Mountain House in one of the most picturesque parts of the Eastern Slopes of the Canadian Rockies.

Upriver from Big Horn is Abraham Lake, the reservoir whose development in the 1970s flooded much of Stoney traditional land that extends into the legendary Kootenay Plains through which the David Thompson Highway passes.

While at Big Horn, we were embraced by Jacob and Mary House.

The couple were born in the later 1800s. Those were the challenging, self-reliant days soon after the great Ta-Otha (tah-OH-thah, “Moose Killer”) of the Stoney First Nation led a band of his people away from the Indian agent-controlled reserve at Morley, and into the freedom of the Kootenay Plains. This was an area rich in moose, elk, deer and big horn sheep – an area of fenceless expanses where horses could graze and people could set up tepees in a respectful relationship among each other, the land, and the Creator.

Indeed, so warmly did the House family welcome us that it wasn’t long before Jacob decided to call me mîchîksi (meen-CHEENK-shee, “my son”) and told me I was to call him ade (ah-DAY, “my father”). He also gave me the name Tatâga Thkan (tah-TAHNG-gah THKAHDN, “White Buffalo”), with the wish that I, like my new namesake, would be a harbinger of hope for the community.

Since naming is so important in the Stoney way, he also told me the story of how he got his own name.

One cold, snowy winter day when he was still just a babe in arms, his mother had taken him outside with her and some of the other women while they set up tepee poles. She had wrapped him in his yokiba (yoh-KEE-bah, “moss bag,” a “bunting” with its unique disposable diaper of soft, absorbent moss) and placed him on a knee-high stack of blankets above the snow.

The women were so involved in their work they hadn’t noticed that he’d managed to wiggle his arms free and roll himself off the blankets. When one of the women went to check on him, she found him face down in the snow. Picking him up, she snuggled his very cold hands in her bosom and called out to his mother: “Eeeee, dathagach!” (dah-THAH-gahch, “he’s frozen!”).

Obviously they succeeded in thawing him out. A name was in order, however, and he was known ever after as Dathagen (dah-thah-GAYDN, “Frozen One”).

Well, that may have been his name, but his relationship toward us was anything but frozen. So, thank you, Ade – and thank you, Stoney Country – for the warm welcome you’ve shown my family and me over the past 50 years. May I practice that same warmth of hospitality toward all I meet along life’s way and be a harbinger of hope for many.

© 2015 Warren Harbeck

JoinMe@coffeewithwarren.com