Good day to live — and to loveCOFFEE WITH WARREN, with Warren Harbeck |

|

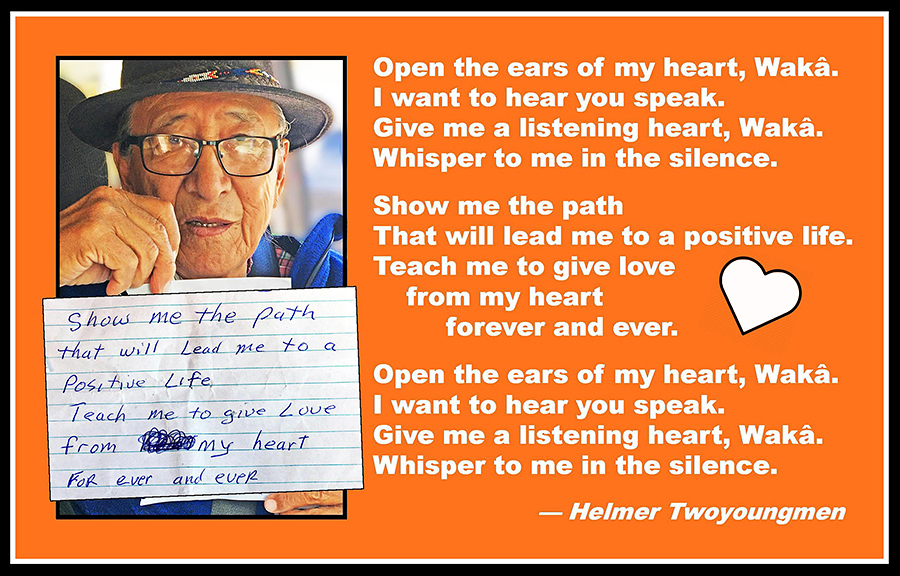

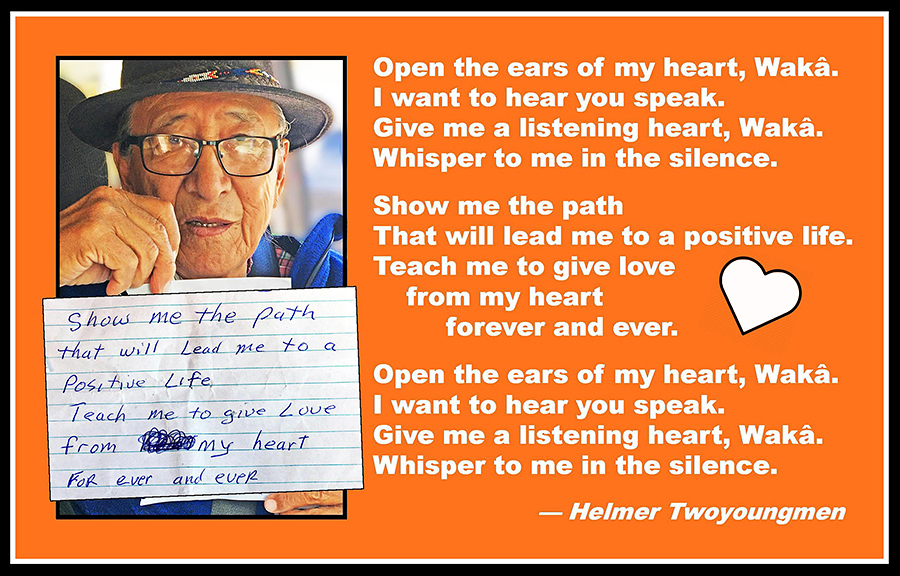

Headlines lately have left no doubt that two culprits have been having an especially disturbing impact on life among the Stoney Nakoda First Nation at Morley: the recent discovery of the previously undocumented remains of 215 students at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, and the problem of drugs and drug dealers in the community. Popular Stoney Nakoda motion picture actor Helmer Twoyoungmen brought to my attention some of his own concerns recently in a most intriguing way: he wrote a poem that he’s sharing with our readers this week. First, a little background on Helmer, who’s been like mîthûgan (“my little brother”) to me since the late 1960s. He’s a man who pursues his dreams, whether as an intercultural interpreter, producer of traditional music and musical instruments, or in on-screen roles in North and South America, Europe and Australia. One motion picture that had a particularly big impact on launching his dream of becoming an actor, Helmer says, was co-starred by his hero, the late Chief Dan George (as Old Lodge Skins, an Elder of the Cheyenne Nation, the “Human Beings”). Outdoor scenes in Little Big Man, the Custer-era western, were filmed in 1970 just south of the current Chief Goodstoney Rodeo Centre at Morley, not far from Helmer’s home. He visited the set during a shoot and was so taken with Chief Dan George that he determined then and there that he, too, would be in motion pictures. (See Chelsea Kemp’s Oct. 19, 2020 Cochrane Eagle article, Benefits of Alberta film industry abound.) You may remember the scene toward the end of the film immediately following a bloody bows-and-bullets battle between Gen. Custer’s forces and the Human Beings when Gen. Custer died just as he was about to shoot co-star Dustin Hoffman (as Jack Crabb, aka Little Big Man). Old Lodge Skins declares about himself, “It is a good day to die,” and lays down on the ground. But after a short wait, he props himself back up and asks, “Am I still in this world?” I sensed a reverse echo of that in the poem Helmer is sharing with us. For him, the current scene at Morley is not about being “a good day to die,” but a good day to live – a day characterized not by bows, bullets and bloodshed, but by love. Troubled by what he was seeing of rivalries and deaths in the drug scene at Morley, Helmer went off to a quiet place by himself to seek guidance from Wakâ, (“the Creator, God”). That guidance came in the form of a poem. He was so taken by that experience, he phoned me, said he’d meet me outside my house and show it to me. Which he did. And as you can see from the accompanying graphic, the guidance Wakâ gave him was anything but vengeful and negative. In fact, it was most positive: “Teach me to give love from my heart forever and ever.” Yes, I can think of all kinds of reasons why I could be overcome with rage and revenge over situations like the discovery of the remains of the 215 children in Kamloops. But Helmer’s prayer offers a positive alternative for why I, too, am still in this world: to commit myself to initiatives that reflect “love from my heart” for the healing of all Human Beings touched by injustice – and to distance myself from any negativity that would threaten to deprive all of us of our God-given humanity. Îsniyes, mîthûgan.

© 2021 Warren Harbeck |